Introduction

Cavities, also known as dental caries or tooth decay, are one of the most common dental problems affecting individuals worldwide. They occur when harmful bacteria in the mouth break down the sugars from the food we consume, producing acids that attack and erode the enamel, the outer protective layer of teeth. Over time, this process can lead to the formation of holes or cavities in the teeth, which can cause pain, discomfort, and even tooth loss if left untreated.

While cavities are preventable, they remain a widespread concern in both children and adults. Understanding the formation of cavities is critical to preventing their development and ensuring that individuals maintain optimal oral health. Additionally, there are several treatment options available for managing cavities, ranging from preventive measures to restorative treatments that aim to repair and protect damaged teeth.

This essay will explore how cavities form, the factors that contribute to their development, the symptoms associated with them, and the most effective treatments available to address tooth decay. By examining the process of cavity formation and treatment options, this essay aims to provide readers with a thorough understanding of this prevalent dental issue and how to prevent or treat it effectively.

Section 1: Understanding Tooth Anatomy and How Cavities Develop

Tooth Structure Overview

- Enamel: The outermost layer of the tooth, made of hardened minerals, which provides protection against decay.

- Dentin: The layer beneath the enamel, softer and more susceptible to decay.

- Pulp: The innermost part of the tooth containing nerves and blood vessels.

- Cementum: The substance covering the root of the tooth, helping anchor it to the jawbone.

The Role of Bacteria in Cavity Formation

- Plaque: A sticky, colorless film of bacteria that constantly forms on the teeth. When plaque is not removed, it hardens into tartar, which can only be removed by a dentist.

- Bacterial Action on Sugars: Bacteria in the plaque feed on sugars from food, producing acids as a byproduct.

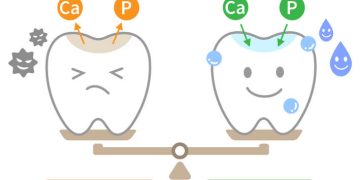

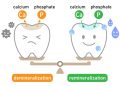

- Acid Production: The acids produced by bacteria dissolve the minerals in the enamel, leading to demineralization and the formation of cavities.

Stages of Cavity Development

- Stage 1: Demineralization: The initial stage of cavity formation, where enamel begins to lose minerals due to acid exposure. This stage is often reversible if caught early.

- Stage 2: Enamel Decay: As the enamel weakens, a visible white spot may appear. If the decay progresses, the enamel may develop cracks or small holes.

- Stage 3: Dentin Decay: Once the enamel is compromised, bacteria penetrate the dentin layer, causing pain and sensitivity.

- Stage 4: Pulp Involvement: If left untreated, the decay may reach the pulp, resulting in severe pain, infection, and the potential need for a root canal or tooth extraction.

Section 2: Factors That Contribute to the Formation of Cavities

Dietary Habits

- Sugary and Acidic Foods: High consumption of sugar, soda, and acidic foods leads to the production of more acid in the mouth.

- Frequency of Eating: Snacking throughout the day or sipping sugary drinks increases the time teeth are exposed to acid, raising the risk of decay.

- Fermentable Carbohydrates: These carbohydrates, like those found in bread, pasta, and fruit, can break down into sugar, feeding harmful bacteria.

Poor Oral Hygiene

- Plaque Buildup: Inadequate brushing and flossing allow plaque to accumulate, leading to bacterial growth and decay.

- Inconsistent Brushing: Failing to brush teeth regularly or thoroughly can result in food particles and plaque remaining on the teeth.

Saliva’s Role in Oral Health

- Saliva Function: Saliva helps neutralize acids, wash away food particles, and provide essential minerals for enamel remineralization.

- Dry Mouth: Reduced saliva flow due to certain medications or medical conditions can increase the risk of cavities, as the mouth becomes more acidic and less capable of neutralizing harmful substances.

Genetic Factors

- Tooth Anatomy: Some individuals may have naturally deeper grooves and pits in their teeth, which can trap food particles and make it harder to clean the teeth, increasing the likelihood of decay.

- Salivary Composition: Genetic factors can also influence the composition of saliva, affecting its ability to protect against cavity formation.

Environmental and Lifestyle Factors

- Smoking and Tobacco Use: Tobacco can contribute to plaque buildup and reduce saliva flow, increasing the risk of cavities.

- Infrequent Dental Visits: Neglecting regular dental checkups and cleanings can lead to undetected cavities and worsening oral health.

Section 3: Symptoms and Diagnosis of Cavities

Common Symptoms of Cavities

- Tooth Sensitivity: Sensitivity to hot, cold, or sweet foods and drinks is often a sign of enamel erosion and the formation of cavities.

- Toothache: A dull or sharp pain in the affected tooth, especially when chewing or biting, may indicate that the cavity has reached the dentin or pulp.

- Visible Holes or Cracks: Cavities that have progressed may present as visible holes or dark spots on the tooth surface.

- Bad Breath: Persistent bad breath or a bad taste in the mouth may occur as a result of decaying food particles and bacteria in the mouth.

Diagnostic Techniques

- Visual Examination: Dentists often check for signs of cavities during routine checkups, including visible holes, discoloration, or wear on the teeth.

- X-Rays: Dental X-rays are used to detect cavities that are not visible to the naked eye, especially those between teeth or below the gum line.

- Laser Cavity Detection: New technology, such as laser fluorescence, can help identify early-stage cavities by detecting changes in the tooth’s structure.

- Dental Probing: Dentists use small instruments to check for soft spots or decay on the tooth’s surface during routine exams.

Section 4: Preventing Cavities

Good Oral Hygiene Practices

- Brushing Techniques: Brushing at least twice a day with fluoride toothpaste, using proper technique and a soft-bristled brush, is essential to remove plaque.

- Flossing: Flossing once a day helps remove food particles and plaque from between teeth, areas that are hard to reach with a toothbrush.

- Mouthwash: Antibacterial mouthwash can help reduce plaque buildup and prevent cavities by killing harmful bacteria.

Dietary Adjustments

- Limit Sugar and Acid: Reducing sugary foods, sodas, and acidic beverages can help protect teeth from harmful acids.

- Balanced Diet: A diet rich in fruits, vegetables, dairy products, and lean proteins provides essential nutrients for oral health, including calcium, vitamin D, and phosphorus.

Fluoride Use

- Fluoride Toothpaste: Fluoride strengthens enamel and helps reverse early stages of tooth decay.

- Fluoride Treatments: In-office fluoride treatments or fluoride varnish applications are available to provide added protection, especially for individuals at higher risk for cavities.

Dental Sealants

- What Are Sealants?: Dental sealants are thin coatings applied to the grooves of teeth, especially molars, to prevent food and bacteria from getting trapped and causing decay.

- Effectiveness of Sealants: Sealants can reduce the risk of cavities in back teeth by up to 80% for a period of several years.

Regular Dental Checkups

- Early Detection: Regular dental visits help detect early signs of cavities before they become significant problems.

- Professional Cleanings: Dentists can remove tartar and plaque buildup that cannot be removed through regular brushing and flossing, helping to prevent cavities.

Section 5: Treatments for Cavities

Fillings

- Amalgam Fillings: Silver-colored fillings made from a mixture of metals, including silver, mercury, and tin, which are durable and effective for large cavities.

- Composite Fillings: Tooth-colored fillings that are more aesthetically pleasing, often used for cavities in visible areas.

- Glass Ionomer Fillings: A material that releases fluoride to help prevent further decay and is often used for fillings in areas that aren’t subjected to heavy chewing pressure.

Crowns

- What Are Crowns?: A crown is a cap placed over a decayed tooth to restore its shape, size, and strength. Crowns are typically used for large cavities or when the tooth structure is severely damaged.

- Materials for Crowns: Porcelain, ceramic, and metal crowns are available, with porcelain providing a more natural look for visible teeth.

Root Canals

- When Are Root Canals Needed?: If a cavity reaches the pulp of the tooth and causes infection, a root canal may be necessary to remove the infected tissue and save the tooth.

- Procedure: The procedure involves cleaning out the pulp, disinfecting the canal, and sealing it to prevent further infection.

Tooth Extractions

- Severe Decay: In cases where the tooth is beyond repair and extraction is necessary, a dentist will remove the tooth.

- Replacement Options: After extraction, patients can consider tooth replacement options like dental implants, bridges, or dentures.

Section 6: Conclusion

Cavities are a preventable yet common dental issue that can have significant consequences for oral health if not addressed promptly. The formation of cavities is a complex process that involves the interaction of bacteria, diet, oral hygiene, and lifestyle factors. By understanding the causes and symptoms of cavities, individuals can take proactive steps to prevent their development and seek effective treatments when needed.

From simple fillings to more advanced procedures like root canals and crowns, a variety of treatment options are available to address cavities and restore the function and aesthetics of affected teeth. Maintaining good oral hygiene, a healthy diet, and regular dental visits are essential for preventing cavities and preserving long-term oral health.

With early detection and the right treatment, cavities can be managed effectively, allowing individuals to maintain strong, healthy teeth and enjoy a lifetime of good oral health.

Discussion about this post