The desire for a confident, radiant smile knows no age limit. Whether you’re in your 30s seeking to correct long-standing imperfections or in your 70s wanting to rejuvenate a worn-down smile, cosmetic dentistry offers transformative possibilities. However, a one-size-fits-all approach is a recipe for disappointment and even failure. The biological changes that occur as we age—in our jawbones, gums, and even the teeth themselves—profoundly influence which cosmetic procedures are advisable, predictable, and sustainable. A treatment that is ideal for a 25-year-old may be contraindicated for a 65-year-old, not because of the number on their birth certificate, but because of the physiological changes that have occurred in their oral environment. This article explores the critical, yet often overlooked, relationship between age and cosmetic dentistry, providing a roadmap for how to achieve stunning, age-appropriate results that are built to last.

1. The Shifting Foundation: The Critical Role of Bone Density

The jawbone is the literal foundation for your smile. Its health and density are paramount for the success of many cosmetic procedures, particularly those involving dental implants.

Youth and Young Adulthood (Teens-30s): During these years, bone density is typically at its peak. The jawbone is robust and has excellent healing capacity. This is an ideal time for procedures like dental implants, as the bone will readily integrate with the implant post (osseointegration), providing a stable, long-lasting foundation for a crown. Orthodontic treatment also tends to be faster, as bone remodeling occurs more readily.

Middle Age (40s-60s): Following tooth loss, bone resorption begins almost immediately. By middle age, individuals who have lost teeth years prior may have experienced significant bone loss in those areas. This can complicate implant placement, potentially necessizing bone grafting procedures to rebuild the foundation first. For those with all their natural teeth, bone density may still be sufficient, but its quality begins to change, becoming less vascular and more brittle.

Later Years (70s and beyond): Natural, age-related bone loss (osteopenia) can occur, even in the jaws. Combined with the cumulative effects of tooth loss and periodontal disease, this can present significant challenges. Placing implants without adequate bone can lead to failure. However, age itself is not a disqualifier. A healthy, active older adult with good bone volume can still be an excellent candidate for implants, but the assessment and planning must be exceptionally thorough.

2. The Receding Frame: Managing Gum Tissue and Esthetics

The gums are the soft-tissue frame for your teeth. Changes in gum tissue quality and position dramatically affect the final aesthetic outcome of any procedure.

Youth and Young Adulthood: Gums are typically more resilient, thicker, and have a better blood supply. They respond well to procedures like cosmetic gum contouring and are less prone to recession following orthodontic treatment or the preparation of teeth for crowns. The “pink-and-white” aesthetic—the balance between gum and tooth—is often naturally ideal.

Middle Age: Gum recession becomes a more common and significant factor. This can be caused by a lifetime of aggressive brushing, clenching or grinding (bruxism), or periodontal disease. Recession exposes the darker, yellower root surface (cementum), creating uneven tooth color and making teeth appear long. This reality must be factored into any cosmetic plan. Placing veneers on teeth with receded gums can result in an unnatural, “too long” appearance or unsightly exposed margins. Treatments often need to focus on addressing the recession first, perhaps with gum grafting, before the final cosmetic restorations are placed.

Later Years: Significant gum recession is the norm rather than the exception. The focus often shifts from creating a “perfect” Hollywood smile to achieving a healthy, natural, and age-appropriate rejuvenation. The goal may be to restore length and volume to worn teeth to support the lips and face, rather than aiming for uniform, bright whiteness. The cosmetic plan must carefully respect the gum line to avoid creating restorations that are aesthetically incongruent with an older face.

3. The Test of Time: Material Durability and Longevity Concerns

A cosmetic restoration isn’t just about how it looks on day one; it’s about how it looks and functions in 10, 15, or 20 years. The choice of material must account for a patient’s age and the physiological stresses they will face.

The Longevity Equation: A 25-year-old getting porcelain veneers must be prepared for the possibility of needing to replace them multiple times over their lifetime, as no restoration lasts forever. For an older patient, the calculation is different. The material chosen should offer excellent durability for their expected lifespan, potentially reducing the need for complex procedures later in life.

Material Selection by Life Stage:

- For Younger Patients: Durable, long-lasting materials like full-contour zirconia for crowns or high-strength lithium disilicate (e-max) for veneers are excellent choices, designed to withstand decades of use. The focus is on maximum longevity.

- For Older Patients: While strength is still important, other factors may take precedence. Softer, less abrasive materials that are gentle on opposing natural teeth can be a wise choice. The treatment plan may also favor less invasive options. For example, direct composite bonding might be a suitable, conservative alternative to veneers for an 80-year-old, as it requires minimal tooth reduction and can achieve a fantastic aesthetic improvement without the commitment of a more permanent restoration.

Accounting for Parafunction: Teeth grinding and clenching (bruxism) is a common issue that transcends age but can cause more damage in older patients with more brittle teeth. Any cosmetic plan for a patient with bruxism, regardless of age, must include a protective night guard to shield the investment in their new smile.

4. The Biological Boundaries: Understanding Age-Related Treatment Limitations

While modern dentistry is remarkably advanced, it cannot always overcome the biological realities of an aging mouth. Recognizing these limitations is key to creating a successful and ethical treatment plan.

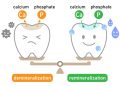

Pulp Chamber Size: The central chamber of the tooth, which contains the nerve (pulp), becomes smaller with age as secondary dentin is laid down throughout life. In a young tooth, the pulp is large, making it more vulnerable to trauma and sensitivity during procedures like tooth preparation for crowns. In an older tooth, the smaller pulp is less sensitive and more protected, which is an advantage. However, it also means the tooth is more brittle and prone to cracking.

Reduced Healing Capacity: Blood flow and cellular regeneration slow down with age. This can mean a longer recovery time after surgical procedures like implant placement or gum grafting. It also means that the risk of complications, such as dry socket after an extraction or post-operative infections, can be slightly higher, requiring more meticulous post-operative care.

Medical Comorbidities: Older patients are more likely to have systemic health conditions like diabetes or osteoporosis, or be on medications that affect oral health (e.g., causing dry mouth). These factors can directly impact the success of cosmetic treatments. A comprehensive medical history review is non-negotiable for older adults to ensure treatment is safe and likely to succeed.

5. The Art of Customization: Age-Tailored Cosmetic Solutions

The most successful cosmetic dentists don’t just treat teeth; they treat people. They tailor the solution to the individual’s biological age, lifestyle, and aesthetic goals.

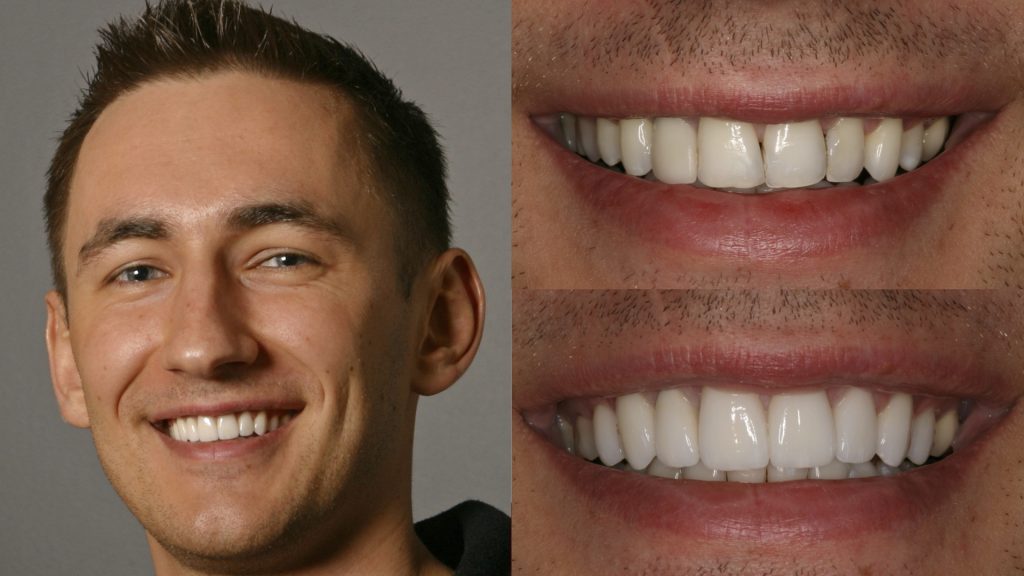

The “Age-Appropriate” Smile Design: A stunning smile for a 70-year-old does not look the same as one for a 20-year-old. It should be softer, with more characterization, slight variations in color, and a flatter chewing surface to account for a lifetime of wear. The aim is rejuvenation, not regression.

Prioritizing Health and Function: For older patients, the cosmetic plan is often integrated with necessary restorative work. The goal is to create a smile that is not only beautiful but also functional, comfortable, and easy to maintain. This might involve combining crown lengthening to restore a decayed tooth, a gum graft to cover a sensitive root, and finally, a porcelain crown to perfect the tooth’s appearance and strength.

A Phased, Conservative Approach: Instead of a complete, invasive smile makeover, an age-tailored plan might be phased over time. It might start with teeth whitening and composite bonding to address immediate concerns, reserving more extensive work like veneers for later, if needed. This conservative approach preserves tooth structure and allows the patient to adapt to their new smile gradually.

Chronological age is just a number, but biological age is a blueprint. A successful cosmetic outcome is not defined by achieving a generic, perfect smile, but by creating a beautiful, healthy, and functional result that harmonizes with an individual’s unique stage of life. By understanding and respecting how age affects the mouth’s foundation, frame, and materials, you and your dentist can co-create a smile transformation that is not only stunning but also smart, sustainable, and tailored perfectly for you.

Discussion about this post