For generations, the process of getting a crown, bridge, or set of dentures was synonymous with a uniquely unpleasant experience: the traditional dental impression. The gooey, thick paste, the overwhelming taste and smell, the tray pressing against the roof of your mouth, and the frantic, gag-inducing minutes of trying to breathe through your nose—it’s a memory that has fueled dental anxiety for millions. But this dreaded ritual is rapidly being consigned to the history books, replaced by a technology that feels like something from science fiction. The intraoral scanner, a sleek, handheld wand that captures a perfect digital replica of your teeth and gums, is fundamentally changing the patient experience and elevating the standard of dental care. This article explores the quiet revolution happening in dental operatories, detailing how these scanners work, the profound benefits for both accuracy and comfort, and the reasons why this transformative technology is not yet in every single dental practice.

1. The Digital Magic Wand: The Technology Behind Intraoral Scanning

So, how does this device replace a physical impression? The process is a marvel of modern engineering, combining optics, software, and real-time data processing.

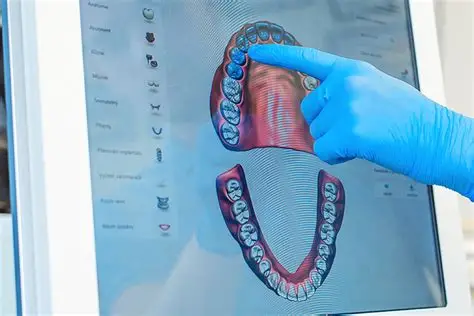

The Process of “Digital Impressioning”: The dentist or assistant glides the small, smooth tip of the scanner over the surfaces of your teeth and gums. As it moves, it projects a safe, structured light pattern (or uses confocal microscopy) onto the surfaces and captures thousands of images per second. These images are not just photographs; they are precise measurements of distance and depth.

Real-Time 3D Modeling: The scanner’s software uses a technology called optical triangulation. By analyzing how the projected light pattern deforms as it hits the complex contours of your teeth, it can calculate the exact three-dimensional coordinates of every point it sees. These millions of data points, known as a “point cloud,” are instantly stitched together by powerful software to create a highly accurate, rotatable, and zoomable 3D model of your mouth that appears in real-time on a chairside monitor.

From Data to Dental Work: Once the scan is complete—a process that typically takes one to two minutes per arch—the digital model is final. This file, which is exponentially more accurate than a physical impression, can then be used in two ways:

- In-Office Milling: Sent directly to a chairside milling machine (like CEREC) to fabricate a crown, inlay, or onlay while you wait.

- Secure Digital Transfer: Electronically sent to a dental laboratory anywhere in the world, where a technician will use it to design and create the final restoration, whether it’s a 3D-printed model for a traditional casting or a digitally designed crown.

2. The Pursuit of Perfection: The Unmatched Accuracy of Digital Models

The primary clinical driver for adopting intraoral scanners is their superior accuracy and consistency compared to traditional methods.

Eliminating the Chain of Errors: A traditional impression is fraught with potential for inaccuracy at every step:

- The Material Itself: The impression material can have bubbles, can tear, or can distort if not mixed perfectly.

- The Removal: Taking the set impression out of the mouth can cause flexing and distortion.

- The Pouring: The dental stone or plaster used to create the model can shrink as it sets.

- The Shipping: Models can be damaged in transit to the lab.

An intraoral scanner bypasses all these steps. The digital file is a perfect, immutable record. It cannot bubble, tear, shrink, or break. What the dentist scans is exactly what the lab technician sees on their screen.

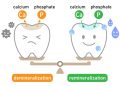

Pixel-Perfect Margins: For restorations like crowns, the most critical area is the margin—the fine edge where the crown meets the tooth below the gumline. A physical impression can struggle to capture this detail perfectly, especially if there is bleeding or saliva. A high-resolution digital scan can capture these margins with sub-millimeter precision, leading to crowns that fit more snugly. A better fit means less chance for leakage, recurrent decay, and gum irritation, ultimately ensuring the restoration lasts much longer.

3. A Revolution in Comfort: The End of the Gag Reflex and Anxiety

From a patient’s perspective, the benefits of intraoral scanning are immediate and profound, transforming a stressful ordeal into a simple, comfortable procedure.

The End of Gagging: This is the most celebrated benefit. Without a large, bulky tray filled with viscous material pressing on the soft palate, the overwhelming trigger for the gag reflex is eliminated. The small, smooth tip of the scanner is far less intrusive, making the process tolerable even for patients with a very sensitive gag reflex.

Enhanced Sensory Experience: Patients are freed from the unpleasant taste, smell, and texture of impression materials. The process is clean and dry. Furthermore, the ability to breathe and speak normally throughout the scan greatly reduces feelings of claustrophobia and loss of control.

Engagement and Transparency: For the first time, patients can see what the dentist sees. As the 3D model builds on the screen in front of them, they can understand the condition of their teeth, see the prepared tooth for a crown, and engage in a discussion about their treatment. This transparency builds immense trust and demystifies the dental procedure.

4. The Engine of the Aligner Boom: Scanners as the Foundation of Invisible Orthodontics

The global explosion of clear aligner therapy, led by companies like Invisalign, would have been impossible without intraoral scanning technology.

Seamless Integration: The digital scan is the direct input for the entire aligner manufacturing process. The scan file is uploaded to the aligner company, where technicians and AI software use it to plan the step-by-step movement of the teeth and design the series of custom aligners.

Superior to Physical Impressions for Orthodontics: For orthodontic cases, capturing the precise alignment of teeth, including tight contacts and rotations, is critical. A physical impression can distort when removed over tightly packed teeth, leading to an inaccurate model and poorly fitting aligners. A digital scan captures the true position without any risk of distortion.

Remote Monitoring: Newer applications allow for “teledentistry” in orthodontics. Patients can be given take-home scanners to periodically capture the progress of their treatment, sending the data to their orthodontist for review without needing to come into the office for an appointment.

5. The Roadblocks to Ubiquity: Understanding the Barriers to Adoption

Despite the clear advantages, intraoral scanners are not yet in every dental practice. The transition from analog to digital has several significant hurdles.

High Initial Cost: This is the single biggest barrier. A high-quality intraoral scanner represents a major capital investment, often costing tens of thousands of dollars, not including the associated software and training. For a small, established practice with a reliable traditional impression workflow, the return on investment can be difficult to justify in the short term.

The Learning Curve: Mastering an intraoral scanner is a new skill. It requires learning new software, understanding optimal scanning paths and techniques, and troubleshooting issues like managing moisture or scanning in deep gum pockets. This initial learning period can be frustrating and time-consuming for the clinical team.

Technological Limitations (Perceived and Real): While scanner technology has advanced dramatically, some veteran dentists remain skeptical that it can truly match the accuracy of a well-done physical impression for every single complex case, such as those involving multiple implants or full-arch restorations. However, this gap is closing rapidly with each new generation of hardware and software.

Practice Culture and Inertia: Changing a long-established, successful workflow is difficult. Dentists and assistants who are highly proficient with traditional impressions may see no compelling reason to change a system that, from their perspective, isn’t broken.

The intraoral scanner is more than just a new gadget; it is a symbol of dentistry’s digital transformation. It represents a move towards a future that is more precise, more efficient, and overwhelmingly more patient-friendly. While cost and learning curves remain, the trajectory is clear. The days of gagging on impression material are numbered, soon to be a curious, unpleasant memory, replaced by the quiet hum of a digital wand building a perfect smile on a screen.

Discussion about this post